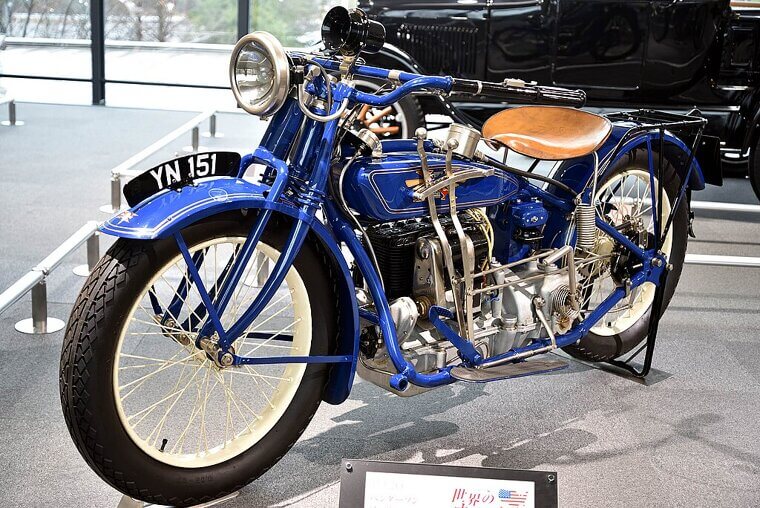

Crocker

Crocker was short-lived but unforgettable- American muscle incarnate on two wheels. They slapped V-twins into frames that demanded respect (and occasionally terrified riders). Their bikes were rare, fast, and unapologetically loud. Production ceased in the ’50s, leaving collectors with one thought: “Why wasn’t I born richer?”

Brough Superior

Known as the “Rolls-Royce of Motorcycles,” Brough Superior wasn’t just a bike - it was a flex. Hand-built perfection from the 1920s, these machines roared with aristocratic arrogance and oil leaks in equal measure. T.E. Lawrence (yes, “Of Arabia”) adored his. Modern bikes owe their performance polish to Brough.

Vincent HRD

Vincent didn’t make motorcycles; they made land-based lightning. The Black Shadow could top 150 mph back when cars still had wooden dashboards. These bikes were gothic, glorious, and terrifyingly quick. When production ended in 1955 the world quietly mourned, though every superbike built since still whispers, “Vincent got there first.”

Excelsior (UK)

Excelsior began humble, building bicycles before diving headfirst into the growling chaos of engines. They became Britain’s first motorcycle manufacturer - a title that aged like fine ale. Excelsior machines were sturdy, sensible, and slightly smug about it, leaving behind a blueprint of British grit.

Indian (original Company, Pre-Revival)

Before Harley hogged the spotlight, Indian ruled the American road. With sweeping fenders and V-twin thunder, these bikes made the open highway a religion. Mismanagement and wartime chaos sent them to the scrapyard; the modern revival’s flashy, but it rides on the bones of a legend that burned rubber first.

Ariel

As the café racer’s cheeky ancestor, Ariel mixed elegance with mischief. They gave us the Square Four, a four-cylinder marvel that purred like a kitten but had a tiger’s bite. Financial storms eventually sent them under; still, Ariel’s spirit lingers every time innovation looks pretty.

Matchless

With a name like Matchless, the company set itself up for high expectations… and mostly delivered. These London-built bikes balanced elegance and muscle like a tuxedo with knuckle dusters. Eventually merged and muddled into oblivion, its classy swagger still echoes down every polished crankcase.

AJS (original Company)

AJS started as a family affair, crafting bikes with precision and pride. Their race victories made them household heroes, but competition and corporate chaos clipped their wings. Yet their racing DNA lives on, a reminder that even the humblest garage can dream up a speed demon.

Velocette

Velocette built motorcycles that didn’t shout; they purred. Handmade, refined, and famously reliable, these were bikes for riders who appreciated understatement over flash. They won Isle of Man TTs with quiet confidence and elegant engineering. When the company folded, it wasn’t failure — it was heartbreak.

Norton (original Company, Pre-Revival)

Norton roared like a pint-fueled poet - fierce, passionate, and occasionally self-destructive. The Commando became an icon, its engine vibrating with the spirit of rebellion. But mismanagement and market shifts toppled the titan. Even so, “Norton” still sends a shiver through riders’ bones.

Panther

Panther’s bikes were stubborn beasts: slow, strong, and built like oak furniture. Their big singles could haul a sidecar full of groceries or a family of five if you were daring. When it vanished, the roads felt a little less rugged (and a lot quieter).

Douglas

Douglas bikes came from Bristol, powered by flat-twin engines that hummed like an angry wasp. Light, nimble, and mechanically clever, they found fame in racing and dispatch work alike. Douglas faded into nostalgia. Its engineering brilliance helped define the very shape of modern bikes.

Royal Enfield (UK Company, Before Indian Revival)

Before the Indian revival, Royal Enfield was the plucky Brit that wouldn’t quit. “Built like a gun” wasn’t just a slogan; it was a warning. Their rugged designs and military service made them icons of reliability. When production shifted east, the soul stayed behind in Britain’s rain-soaked lanes.

Sunbeam

Sunbeam bikes looked like they’d arrived from the future… if the future wore tweed. Known for their silky engineering and posh reputation, they catered to riders who liked their thrills served on fine china. Even though post-war austerity dimmed their shine, Sunbeam’s elegance still gleams in luxury touring bike DNA.

Rudge-Whitworth

Rudge was all about innovation: four-valve engines, linked brakes, and more cleverness than a professor’s pocketbook. Their racers dominated the 1930s, earning trophies and admiration in equal measure. Financial trouble finished them off; nevertheless, every performance bike since has borrowed a page from Rudge’s dusty notebook.

Scott Motorcycles

Scott built two-strokes before they were cool (or even well understood). Their bikes were water-cooled, futuristic, and occasionally temperamental. They won races, baffled engineers, and inspired legends. Though Scott’s production sputtered out, their spirit still lingers in every smoky roar of a two-stroke engine.

Henderson

Henderson built four-cylinder bikes when most makers were still debating which leg to kickstart with. Sleek, long, and surprisingly fast, they were the Cadillacs of the 1920s asphalt. Riders loved them for power and smoothness and though Henderson’s flame flickered out, four-cylinder dreams still owe them much.

Ace Motorcycles

Ace was basically the “cool uncle” of motorcycling: stylish, bold, and slightly reckless. They gave the world the iconic V-twin that inspired decades of American design. Though long gone, Ace lives on in every deep-throated rumble and every rider who secretly dreams of roaring down Route 66.

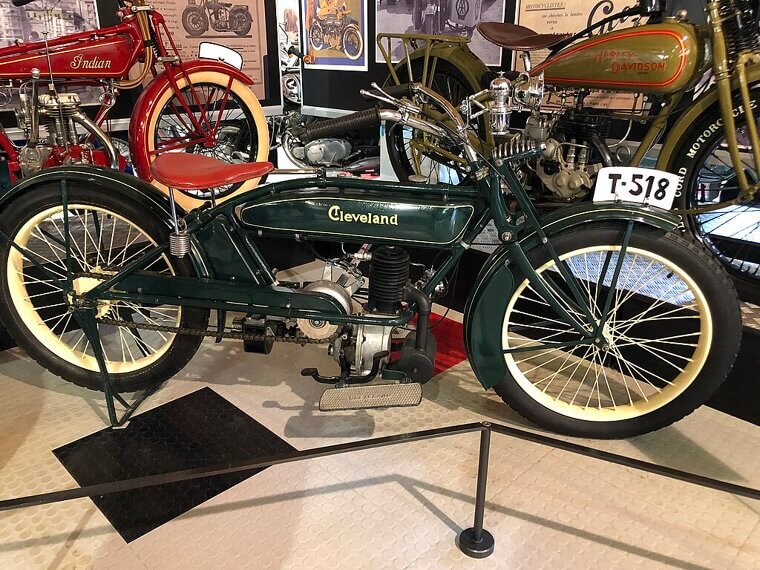

Cleveland Motorcycle Manufacturing Company

Cleveland bikes were plucky, dependable, and made in the heart of Ohio, a state better known for corn than cornering. Their two-strokes and V-twins worked hard and rarely complained until economic shifts and stiffer competition pushed them aside. Every practical, get-things-done bike owes a nod to Cleveland’s work ethic.

Pope Motorcycles

Pope made motorcycles before they were considered sensible. They experimented with engines, frames, and ideas that seemed ahead of their time… and sometimes outright ridiculous! Short-lived but influential, Pope’s creations nudged the industry forward, proving early on that thinking differently can sometimes make history.

Flying Merkel

Flying Merkel was flamboyance on wheels: bright paint, sleek lines, and a name that promised velocity and drama. They raced, wowed crowds, and occasionally startled pedestrians. But financial turbulence grounded them; today, Flying Merkel is mostly a storybook legend, a reminder that style can outlast even the strongest engine.

Simplex

Simplex lived up to its name with straightforward engineering and quietly reliable bikes. They didn’t make headlines, but riders trusted them. In a world chasing speed records and race wins, Simplex was the humble friend who showed up rain or shine. They live on in those who value dependability.

Merkel-Light

Merkel-Light was the little sibling of the Flying Merkel, aiming for nimble practicality over showy spectacle. Light, clever, and mechanically sharp, they tackled city streets and country lanes alike. They never became stars, but their innovation proved that sometimes the quietest machines leave the biggest marks.

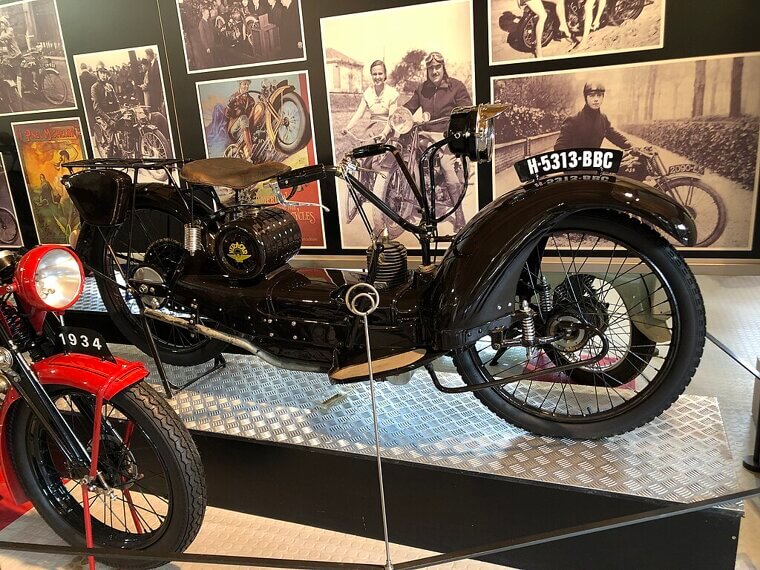

Ner-A-Car

Ner-A-Car looked like a motorcycle, handled like a car, and confused pedestrians everywhere. Its hub-center steering and quirky frame made it a rolling conversation piece. Not everyone appreciated the concept, but the adventurous few loved the novelty. Though production stopped decades ago, thinking sideways still put them miles ahead.

Rex-Acme

Rex-Acme thrived in the 1920s and 1930s with solid, reliable machines that could be counted on for commuting or racing. Their riders were loyal, their engineering competent, and their flair quietly British. When the company faded, they left a blueprint for motorcycles that balanced style, endurance and reliability.

Coventry Eagle

The kind of brand that smelled of damp cobblestones and determination,Coventry Eagle bikes were elegant, sporty, and occasionally stubborn - perfect for riders who liked charm with a side of unpredictability. When competition caught up, Coventry Eagle quietly folded, leaving behind motorcycles that still whisper “British grit” to anyone who listens closely.

New Imperial

A poet among the British motorcycle industry: delicate engineering, beautiful lines, and engines that hummed like a well-tuned violin. New Imperial bikes raced, wowed and innovated… until the harsh realities of the 1930s shuttered their factory. Today, their name survives in whispered reverence and a few gleaming classics tucked into private garages.

Francis-Barnett

Francis-Barnett loved making small, reliable bikes for the everyday rider. Lightweight, nimble, and surprisingly spirited, they were the “can-do” motorcycles of postwar Britain. Affordable and unpretentious, they powered commuters, racers, and weekend adventurers alike. When they disappeared, a generation of riders lost a trusty friend - one that rarely let them down.

James Motorcycles

Priding themselves on practical simplicity and dependable fun, James Motorcycles made lightweight machines that could navigate city streets or country lanes with ease. They weren’t flashy, they weren’t arrogant, but they were loyal companions. Production ceased long ago; however, every practical bike today carries a whisper of James’ modest genius.

Humber Motorcycles

Humber started life making bicycles, then seamlessly jumped into motorbikes. Known for solid builds and reasonable reliability, their motorcycles carried riders through wars, commutes, and adventures alike. Eventually, the market moved on, but Humber’s contribution to early motorcycling innovation and versatility remains undeniable; a sturdy bridge from pedals to pistons.

Clyno

Clyno bikes were quirky, clever, and slightly underappreciated. From 1909 to the mid-1930s, they churned out practical machines that quietly earned loyal fans. They never sought fame, but their craftsmanship and reliability nudged the British motorcycle scene forward, leaving a trail of subtle influence for engineers and riders alike.

Wooler

Wooler specialized in unusual engineering and clever designs, often sporting flat-twin engines in innovative layouts. Their bikes were curious, inventive, and occasionally frustratingly ahead of their time. Though they didn’t survive commercially, Wooler left behind a legacy of bold thinking that still inspires unconventional motorcycle design today.

OK-Supreme

Their name sounded like a promise and OK-Supreme delivered, crafting robust, dependable motorcycles that could tackle daily life or the odd racing track. Lightweight and efficient, they catered to riders who valued engineering integrity over flash. When the company disappeared, enthusiasts retained admiration for bikes that quietly did everything they were supposed to.

Montgomery Motorcycles

Montgomery’s machines were the unsung heroes of British roads: competent, well-built, and designed for everyday use. Their engines purred, their frames held true, and their riders loved them for reliability. Although time and competition erased them from showrooms, Montgomery’s spirit lingers in any bike that values substance over spectacle.

J. A. Prestwich Industries

J.A. engines powered more motorcycles than most brands could ever dream of. From speed records to sidecar racing, their mechanical hearts pumped life into countless machines. Though the company itself faded, their engines continued to roar across decades, reminding everyone that sometimes the heart of innovation beats quietly, inside someone else’s frame.