Nissan Fairlady Z 432 (1969–1973)

To early owners, the Z 432 was simply an expensive vehicle, a Fairlady with racing hardware and an intimidating price tag. Many opted to sell when maintenance became demanding or when simpler Zs seemed more sensible. What they let go of, quietly and efficiently, was one of Nissan’s purest homologation specials. Today the 432 is treated as automotive scripture, its market value a constant reminder that rare engineering is only obvious in hindsight.

Honda NSX (First Gen) (1990–2005)

The original NSX made supercars usable and daily drivers feel slightly inadequate. Owners bought them for precision, reliability, and that unmistakable mid-engine poise. Then came life: kids, mortgages, the need for back seats. The NSX was sold as the “responsible” move. Decades later, when values surged and admiration turned into awe, those same owners learned a harsh truth. Responsibility ages poorly when it’s parked next to a supercar you used to own.

Toyota 2000GT (1967–1970)

Once considered “just a pretty old Toyota,” the 2000GT was quietly sold off by owners who assumed its value had already peaked. It hadn’t. Not even close. With fewer than 350 built, this hand-assembled grand tourer would go on to become Japan’s first true global supercar icon. Many early sellers walked away with respectable money at the time… and later watched auction results climb into the millions. Today, they miss both the car and generational wealth.

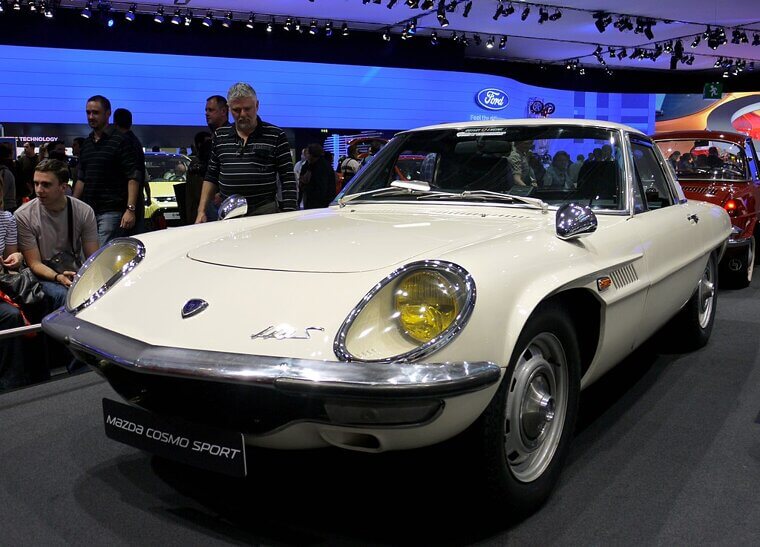

Mazda Cosmo Sport 110S (1967–1972)

The Cosmo was rotary royalty before the world quite knew what that meant. Early buyers enjoyed its science-fiction looks and oddball engine, then moved it along when parts got fiddly and patience ran thin. At the time, it was just an eccentric sports car with quirks; now it’s a crown jewel of Mazda history. Former owners get to enjoy the rare pleasure of saying, “I had one,” followed immediately by, “ and I shouldn’t have sold it.”

Nissan Skyline GT-R “Hakosuka” (1969–1972)

In the ’70s and ’80s the Hakosuka was fast, loud, and… used. Many were raced hard, modified wildly, and sold off cheaply to make way for newer performance toys. It was a hero on track but still just an old sedan to most buyers. Decades later, collectors treat surviving examples like mechanical samurai relics. Those who sold theirs cheaply still hear the echo of straight-six thunder (followed by the quieter sound of financial regret).

Nissan Skyline GT-R R32 (1989–1994)

When the R32 was fresh, owners knew it was special; they just didn’t know it was world-shaking! This was the vehicle that embarrassed supercars, terrorized touring car championships, and rewrote the word “affordable performance.” In the 2000s, many were sold off for practical reasons: space, family, patience for constant temptation. Years later, as values exploded, former owners realized they hadn’t sold a used sports car - they’d sold a legend in mid-sentence.

Nissan Skyline GT-R R33 (1995–1998)

For years, the R33 lived in the shadow of both its famous predecessor and its flawless follow-up. It was larger, heavier, and unfairly branded “the awkward middle child.” As a result, many owners cashed out early, assuming it would always trail behind the R32 and R34. Then the market matured. Collectors re-examined its Nürburgring pedigree, its refinement, its raw capability. Those who sold cheap learned an expensive lesson: history is rarely kind to underestimating the middle act.

Nissan Skyline GT-R R34 (1999–2002)

For a brief, foolish moment in the mid-2000s, the R34 GT-R was simply “that cool Skyline you could still afford.” Owners sold them to fund houses, families or supposedly “wiser investments.” Then the internet did what it does, and the R34 ascended into digital godhood. Movies, games, and myth combined into a perfect storm of value. Today, former owners don’t just regret selling the car; they regret selling front-row seats to their own financial miracle.

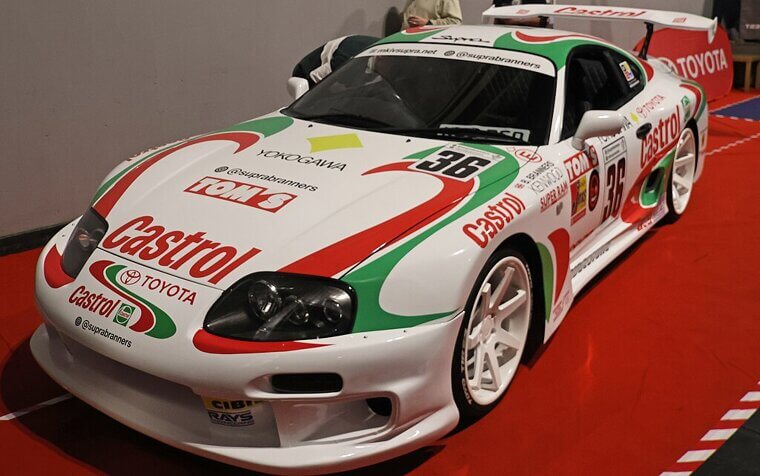

Toyota Supra Mk IV (A80) (1993–2002)

The Supra’s tragedy is that it survived long enough to be treated carelessly. For years it was a used performance bargain: quick, capable, and endlessly modified. Many were sold to chase newer thrills, assuming supply would always outpace sentiment… then production ended. Tuning culture exploded. Original examples vanished. Values went vertical. Now, the same people who once complained about its weight quietly scroll auction listings like astronomers watching a star they used to own drift out of reach.

Mazda RX-7 FD (1992–2002)

The FD RX-7 seduced with beauty and punished with maintenance. Twin turbos, heat, and finely-tuned tolerances made ownership feel like a glamorous part-time job. Many owners sold theirs out of mechanical fatigue rather than financial foresight. At the time, it felt sensible. Years later, as clean examples became rare and prices climbed into sports-car royalty territory, former owners realized they’d walked away from one of the most perfectly balanced driver’s cars Mazda ever dared to build.

Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution VI Tommi Mäkinen Edition (2000)

Built to honor rally dominance, the TME was never meant to be subtle. It was loud in color, sharp in motion and unapologetically focused. Early owners often treated it like just another fast Evo: used hard, sold quickly and replaced easily. Nobody predicted it would become the Evo that collectors would someday whisper about. Former owners get to remember the thrill of ownership alongside the quiet realization that limited editions rarely stay replaceable.

Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution IX (2005–2007)

The Evo IX was the last of a dying breed, though hardly anyone realized it at the time. It was brutally quick, mechanically honest, and unfiltered in a way modern performance cars now politely apologize for. Owners sold them confidently, assuming something just as raw would always exist down the road. It didn’t. When electrification crept in and manuals began their retreat, the Evo IX quietly transformed into a farewell letter to a more nostalgic time.

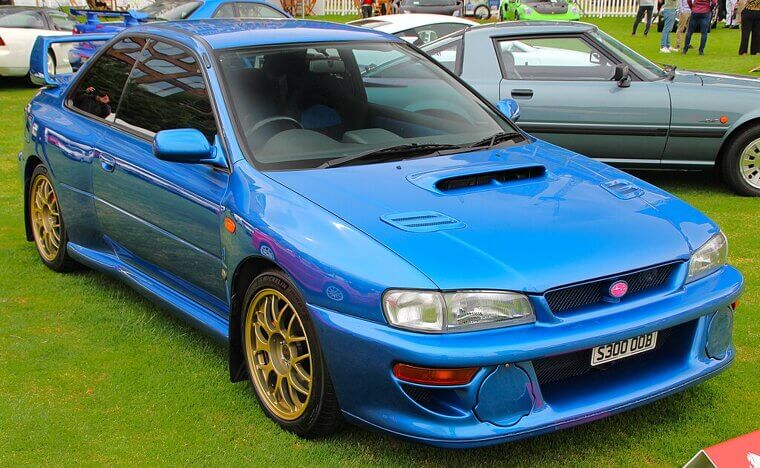

Subaru Impreza 22B STI (1998)

When the 22B arrived, it seemed outrageous in all the wrong ways: expensive, stiff, loud, and wildly impractical. Some early buyers flipped them thinking (incorrectly) that the hype would fade. With only 424 built and rally pedigree baked into every panel, the 22B became Subaru’s untouchable icon. Today it commands supercar money while previous owners stare at photos like archaeologists examining something they once casually parked outside a coffee shop.

Subaru Impreza WRX STI GC8 (1994–2000)

Once upon a time, the GC8 was simply the fast car your friend owned. Raw, noisy, and endlessly tuneable, it was loved hard and sold easily. Many passed through several hands without ceremony until motorsport nostalgia surged, clean examples dried up, and suddenly every surviving GC8 became “the one everyone should have kept.” Former owners remember the turbo flutter fondly (followed by the dull ache of realizing they let go of peak analog Subaru).

Toyota AE86 Sprinter Trueno / Corolla Levin (1983–1987)

For years, the AE86 was an inexpensive, lightweight trainer car - perfect for learning to slide, modify, and occasionally misjudge your own talent. They were crashed, stripped, and sold without much ceremony because they were plentiful and cheap. Then drifting exploded globally, pop culture took over and prices went feral. Owners who once sold running AE86s for pocket change now watch rusted shells sell for fortunes and quietly question every financial decision they made in the ’90s.

Nissan Silvia S15 (1999–2002)

The S15 arrived late and left early, which is part of its tragedy. For a brief window, it was simply an excellent driver’s car: sharp steering, perfect balance, turbocharged charm. Many were exported, modified, thrashed, and resold like expendable fun. Nobody expected it to become the final, most refined expression of Nissan’s legendary Silvia line. Years later, as clean examples vanished and prices climbed skyward, sellers realized they hadn’t moved on.

Honda S2000 (1999–2009)

At the time, the S2000 felt plentiful; It was loud, high-strung, and begging to be revved into the stratosphere, so it seemed destined to be replaced by something equally wild. Owners sold them casually, confident Honda would always build another unhinged roadster… until it stopped. As naturally aspirated performance vanished and manuals thinned out, the S2000 became a mechanical time capsule. Former owners now speak of 9,000 rpm the way sailors speak of lost horizons.

Toyota MR2 SW20 (2nd Gen) (1989–1999)

The second-generation MR2 delivered mid-engine balance to ordinary people with extraordinary confidence. For years, it lived in an uncomfortable middle space: too exotic for commuters, not prestigious enough for collectors. Many owners tired of its quirks and sold it cheaply for something “easier.” Then tastes shifted; clean SW20s climbed in value, and those who once dismissed theirs as inconvenient learned that true balance is rarely appreciated in real time.

Mazda RX-3 (1971–1978)

The RX-3 spent decades as a scrappy rotary underdog. It was fast, simple, and gloriously impractical, which meant many were raced into oblivion or sold off without sentiment. For a long while, it was merely old. Then it became rare. Then it became important. As collectors began tracing Mazda’s rotary bloodline backward with reverence, the RX-3 rose from obscurity into serious desirability. Former owners now watch auction results with the uneasy feeling of forgotten greatness found too late.

Honda Integra Type R DC2 (1995–2001)

Once upon a time, the DC2 Type R was “just” the sharpest front-wheel-drive car you could buy. Owners drove them hard, modified them freely, and sold them without ceremony for something newer and heavier. Nobody imagined that lightweight, naturally aspirated precision would become endangered. As pristine examples vanished and legends grew louder, values climbed with surgical precision. Former owners now carry a very specific regret: they sold one of the greatest handling cars ever built for something “newer.”